Capturing Moments

with artist Tony Sowersby

Tony Sowersby captures wisps of dawning sunlight and reflections of gathered puddles on the road that swirl falling colour, of hope. All around us, enveloping us, is change, with subtlety and force, gentleness and speed. Many among us are not aware, do not take moments to look, and not only look and glance, but see and marvel, ponder and imagine. This is one of Tony’s great gifts. He is a perspicacious observer. He is perpetually curious. From satire, to social commentary, to the human condition, to the seasons, a moment of changing light at dusk, of the ineffable beauty awaiting discovery in the everyday- Tony’s gift is capturing moments, being thoughtful, finding humour in sombre realities and in the nonsensical. He forges memories, and honours loved ones. He is an artist.

In high school, at Salesian College in Chadstone, way back when it was paddocks and family homes with front and back gardens, Tony was growing up. He did art in year seven, but then it was put aside as the subjects deemed to be more important were brought to the fore. Tony was told that if he wanted to take part in art classes, that was for after school, or the weekend. He stuck with it. Michael Connolly, who later became a cartoonist at The Age newspaper, was a year older than Tony. He was a natural and compelled Tony to show up. Tony wanted to see and watch what Michael created. He too wanted to make something.

In year eleven, art was once again reinstated as an option in the curriculum, but Tony said that he was told by one of the priests that he was too academic to waste time on art. He did for a time consider leaving the school but knew that it would come up at cost. He did not want to let his parents down, and anyway, his friends were the best part about school. He forged ahead.

So it was that Tony attended Monash University in his first year out of school, studying Law. He used to draw the lecturers:

“It’s perfect because they are there in front of you, they’re not moving too much and I would sit there and draw them.”

Law was short lived, Tony’s interest waned. He dropped out and worked various jobs, saving, before he headed off for Europe at the start of September in 1974.

“It was massive. I was 19. The flight took thirty-something hours, it was a DC8, so there were only two seats on either side but you had more leg room in those days. There were no films or anything, you just read. We landed in Singapore, we landed in Bangkok, we landed in Tehran and we landed in Rome.”

It cost Tony $320 dollars to get there.

“I thought it was great.”

“It was only one-way because I didn’t know whether I would come back to Australia or not. I took $1,200 dollars which was a lot more money in those days but still not a lot of money.”

The trip left an indelible mark on Tony. He went to lots of galleries. Most of them were free back then.

“I just saw heaps of stuff.”

“No one knew where you were and ringing up cost a fortune, a lot of money so phone calls were rare.”

There was a strong degree of isolation, one that many of us would not know now. People would send letters, the poste restante system, and hopefully Tony would show up and pick them up but sometimes not, depending where in the world he was.

“I loved all of it, even the bit where I had to work. When we went up to Shetland and we were working up there. The fact that we stayed in these two crap, cotton tents near the Arctic Circle, almost. We wore everything we owned. Seriously. We would put on extra clothes to go to sleep.”

Hearing Tony speak of his travels, it seemed that he enjoyed the freedom, the books, the art, the adventure, the camaraderie.

He said that things were winding up towards the end. It was sheer luck that they made it home.

“We had been working up at Shetlands, we were working as laborers- seven days a week, there were four 12 hour days and three eight hour days, so we were really bulked up and fit. I can remember on the way back from Shetland to London we went via the Lake District and we were carrying our packs that had everything it in. I think it was 25-30 miles a day, carrying our stuff and that wasn’t even on tracks. If we hadn’t been that fit, I don’t know what would have happened to us on the way home. It was like we did pre-season training.”

They lost a lot of weight. It was time to head home.

“When we got on the plane at Singapore airport we had 10 cents between us, 10 Singapore cents, which was 3 Australian cents, between us, so we timed our money exactly. We timed it perfectly. That was Christmas day, we went to the airport and they said ‘you’re not on the plane’ and we had 3 cents so he said ‘wait there and we’ll see if two people cancel’. Two people did and that’s how we got home.”

Art was still Tony’s hankering and when he arrived home, his art studies came to the fore, at first in an unconventional way.

“When I got back at the start of ’76, I knew I wanted to do art and I was not quite sure how to go about it. I don’t know what the process of it was, but my sister was doing year 12 at Avila which is an all-girls school and they had this legendary Nun art teacher, Sister Raymond, and I think she heard about me or something and said I could do year 12 art at the girls school.”

“I was 21, with all these 18 year old girls. It was, yeah, really nice”.

“I used to go there for however many periods a week, three or four periods a week, then the rest of the time I would have free time to draw and they had to do all of the other year 12 subjects. I worked at a local fruit shop.”

From there Tony went to Caulfield Art Institute and with the ongoing support of his family and his wife Carol, Caz as he affectionately calls her, art has been his livelihood, his passion and his one constant.

Every day, he patters out to his studio, a few steps from the backdoor. It is awash with natural light. The trees and birds outside peer in. The local beach is just over the fence. The long stretch of sand has provided a reliable show for Tony, with the ever changing skies and reflective waters. It’s quiet here. The native plants hug one another and burgeon around the house. A cheery yellow native lives out the front, a gift from friends when his mother died. Last year, Tony and Carol planted sunflowers throughout their front garden. They plan on doing it again this year.

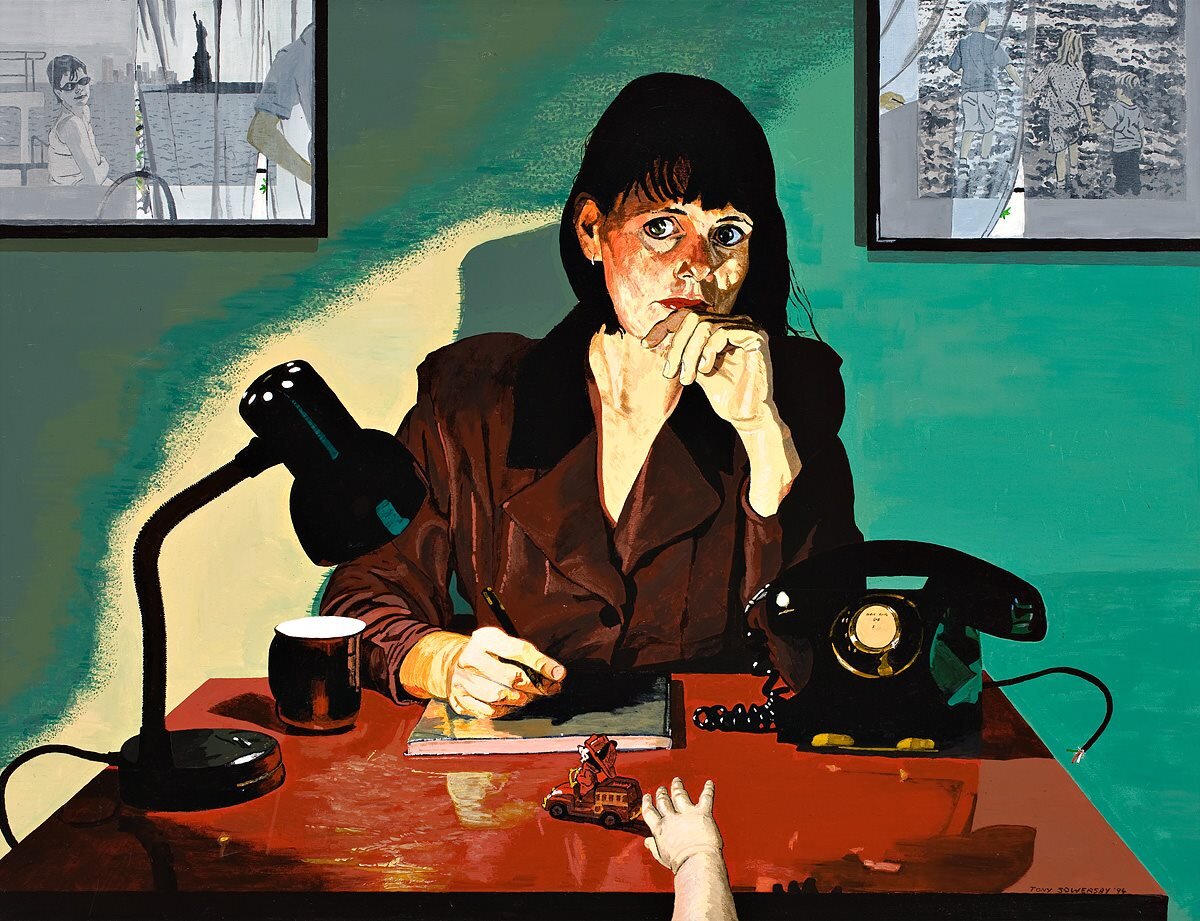

It seems, in many ways, that in order to be a full-time artist, to live it and breathe it, you must enjoy solitude, and you either find someone who pairs with that and you create a balance around it- or you go at it alone, the art as your companion. Tony and Carol are a rare pairing, and chatter away throughout the day, their lives looping and entwining in and around one another’s with contented and unconditional love. Carol champions Tony’s work, and Tony champions Carol. She is often the feature of his works, and many of his artworks are first captured from the passenger seat as they travel, side by side. A whole chapter in his new book is titled, Passenger.

Tony traverses between satire, real life, still life, pop-art, and working with school kids at art inservices. He was a youth worker for 20 years and still does his bit. Now his youngest son Nick, a musician, often accompanies him, working happily on murals together.

His kids he holds dear. A tender moment is captured of his daughter, Bridget, reading at candlelight during a blackout. His son Will is seen in silhouette in his artwork Sunset Cricket.

Tony also digs into the memory bank. He studies old photographs and spends hours tinkering away, recapturing the moment, the time, the connection. His mother and father and siblings, a constant connect, will forever be part of Tony’s ideas, after all, what happens in your childhood, especially when it is a happy and loving one, has a lasting effect.

Tony is releasing a new book titled The Dark Book. After thinking on this for a while, it is not dark in the literal sense, it is dark and what unfurls in the dark- a lot of that is light, reflections, shades, tones.

“…but it’s light, light’s good all the time,” said Tony while flipping through his book.

“It’s what’s happening in them as well, even the purple sky in this particular one, the sky is like that because of pollution and light pollution in the city, it has its own form of beauty but it is not really a good thing.”

“Things that on the surface look like they’re just a visual appeal, but there is actually something more to it, something to do with the light pollution in Melbourne. The whole idea, especially the urban ones, at night you can show, even the most mundane area, takes on something at nighttime that’s got something- you could say it’s not really like that but it is, for half the time.”

“It takes on its own form of beauty and you can learn things from it.”

It is seeing familiar places in different lights, or familiar places in a time of change, that draws Tony in.

In The Dark Book he writes:

Melbourne and its suburbs, the huge, beautiful bay, the land of the Kulin Nation, Naarm, my home since birth, is what I paint and draw more than anything. It is redundant in this Climate Emergency to criticise a place for its inclement weather, but that cliché criticism is still trotted out. Personally, I revel in the winter here, and love to paint it.

Tony has taken a lot of photos in a carpark in Frankston where he goes to the gym. His artwork, The Ineffable Beauty of the Everyday, exhibits this, the beautiful aspects, that requires a pause, a reflection, a way to capture it in art- because it is art. Like an ugly fence that flowers push through, or a drought effected landscape where a trickle of water runs to a tuft of grass, or sunlight falling through a gap in a bland room- there’s beauty prevailing.

“The Ineffable Beauty of the Everyday, that is just a carpark in Frankston- but because of the combination of the light and the rain and probably oil slicks, you get this thing that, only human beings in the last 100 years or so would have seen. It’s new and it comes at a cost.”

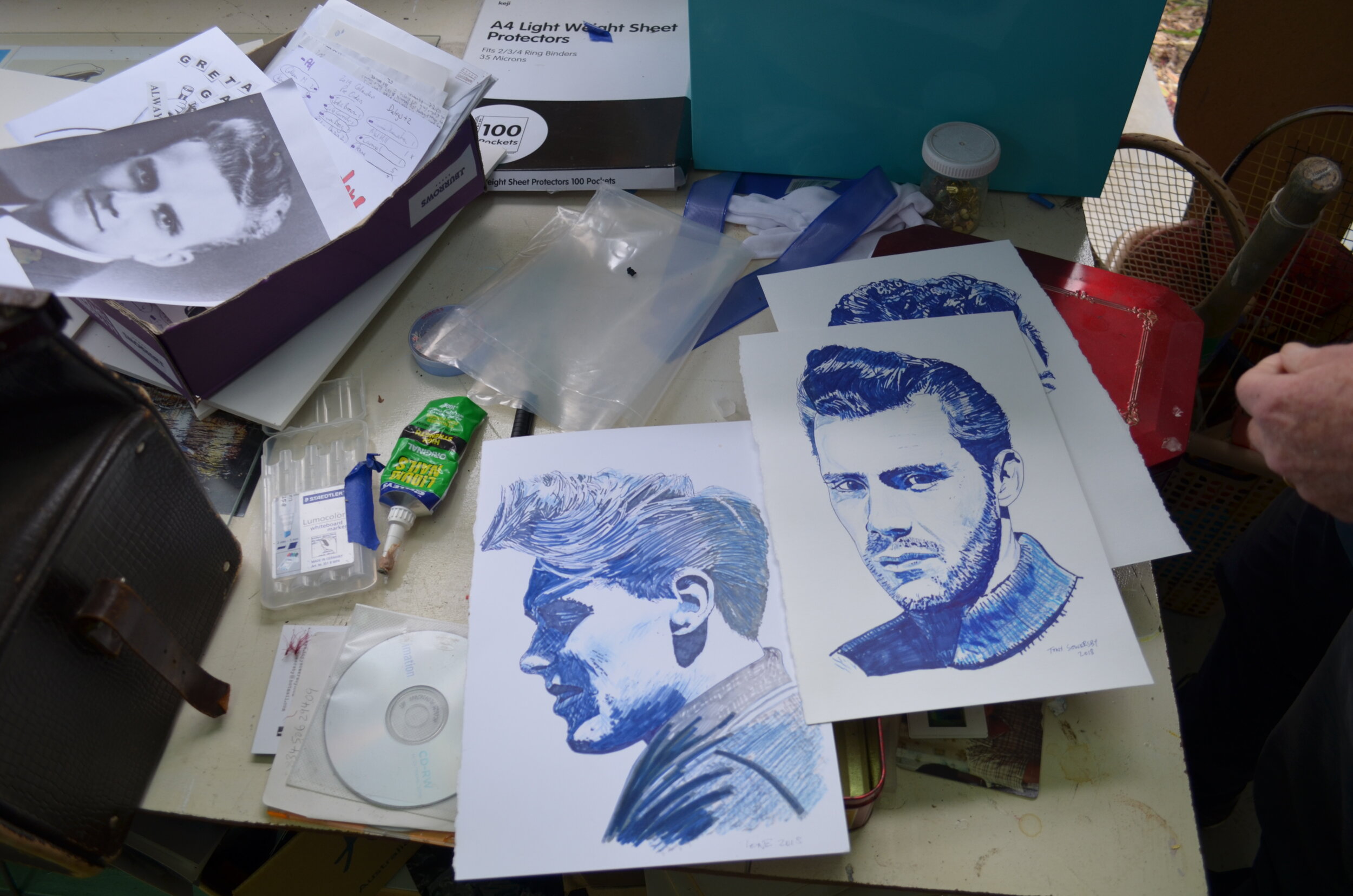

Tony sketches, too. Old film stars, cartoons as such, or else he can get a bit, annoyed. His is a constant doer, every day, out in the studio, drawing, sketching, painting. When he is out, he is a pocketer of ideas, a photographer.

A chance visit to the optometrist almost certainly saved his life.

As an artist he has regular check-ups, but in September 2016, something was awry.

“I wasn’t sure if something was wrong or it was just old age,” laughs Tony after a succession of colds throughout the winter.

“The young optometrist, she did a field test, where you sit your chin on a thing and they have this round screen and you look at all of these lights coming in. It’s like you’re in a video game and every time you see a light come in from the side you press a button and she did one of those on me and she said, ‘something’s really wrong and it’s not your eyes because I have just tested your eyes and they’re fine, it’s behind your eyes’. Then she sent me to an eye specialist and he did the same test but more thorough and then he said, ‘I am sending you straight to a neuro surgeon’.”

Days later Tony was being operated on for a large tumor. It was not cancerous but the neuro surgeon said that it would have burst by Christmas.

“Because the tumor was so big it was effecting my vision, but it was also effecting my immune response.”

“I had no idea that it would be that. I was trying to exercise and all that sort of stuff. I didn’t know my vision was affected until they showed me.”

“The optometrist said ‘you’re an artist you should have noticed’ but when you paint, it is probably the worst job because you are working on one small area at a time.”

Tony was accustomed to focusing his eyesight, and wasn’t aware that the tumor was affecting his peripheral vision.

“If I had of been an elite footballer and people kept hitting me from the side without me seeing them then I might have known, but I had no idea.”

“After the operation I came outside, I didn’t realise so much in the room, but as I came outside and I went strewth! I felt like a fly- oh there’s something over there, faired dinkum, for the first two or three weeks I would just walk around thinking ‘look at that’.”

“1 in 25 people have got one of these. They grow really slowly and lots of people are diagnosed after car accidents, they just haven’t seen a car coming.”

So as luck would have it, Tony got off lightly.

“It made me want to work more, painting.”

Paint on he does. He already has two ideas for upcoming exhibitions, one of new night time paintings, and one of Pop-Art. In his book, The Dark Book, he reflects on the fact that his Mum implored him to look, to find beauty:

I only realized towards the end of her life that my love for the sky came from my Mum. She was always pointing out clouds or colours to me when I was young. The sky is a free show every day. One of the things I love about living in Melbourne is the ever changing and dramatic skies.

His Mum would be proud, as Tony prevails, looking up and around, and locating the interesting, the poetic, the changing, the unsaid- and of course, the light always found in the dark.

“But it’s light, light’s good all the time,” said Tony.

Tony did a retrospective drawing of he and my Father, singing along to A Bird on a Wire by Leonard Cohen. It seems everything links up, the subtle fragments. Thinking on this book, reflecting upon Tony’s reflections, he is finding the light in some of the harder times of life.

Light and night, change- it’s all constant. So is hope and Tony finds that and turns it into art.

“There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” - Leonard Cohen

Article by Sinead Halliday

Artwork by Tony Sowersby

Tony’s new book, The Dark Book, will be launched this Thursday the 28th 6.30-8pm at No Vacancy Gallery, 34-40 Jane Bell Lane (off Russell St) Level 3, QV Building, Melbourne

Visit tonysowersby.com to discover more

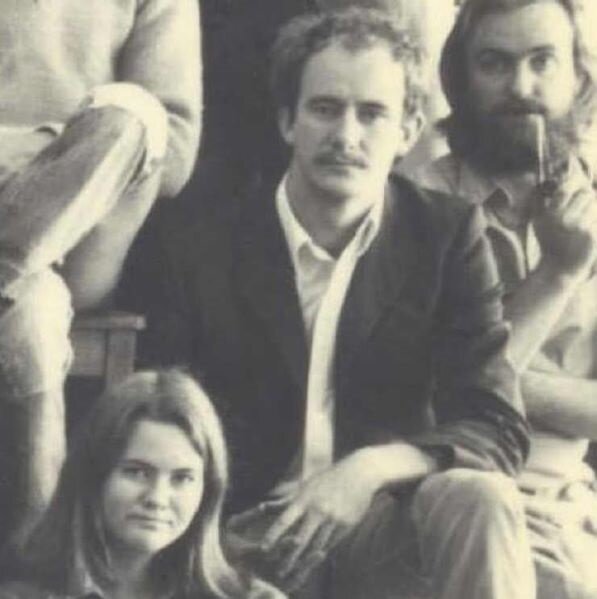

Below is an image of Tony and his fellow art students in the sculpture studio of the Caulfield Institute of Technology, sometime in 1979.